This project, the transformation of a small warehouse into a studio and gallery, summarizes many things. The project is one of a series of projects that deal with typological readymades. Perhaps more importantly, it is one of several projects for which reflected light is a significant protagonist). What is so imminently pleasant about the existing building is the way in which it avails itself to concepts of successive architecture.

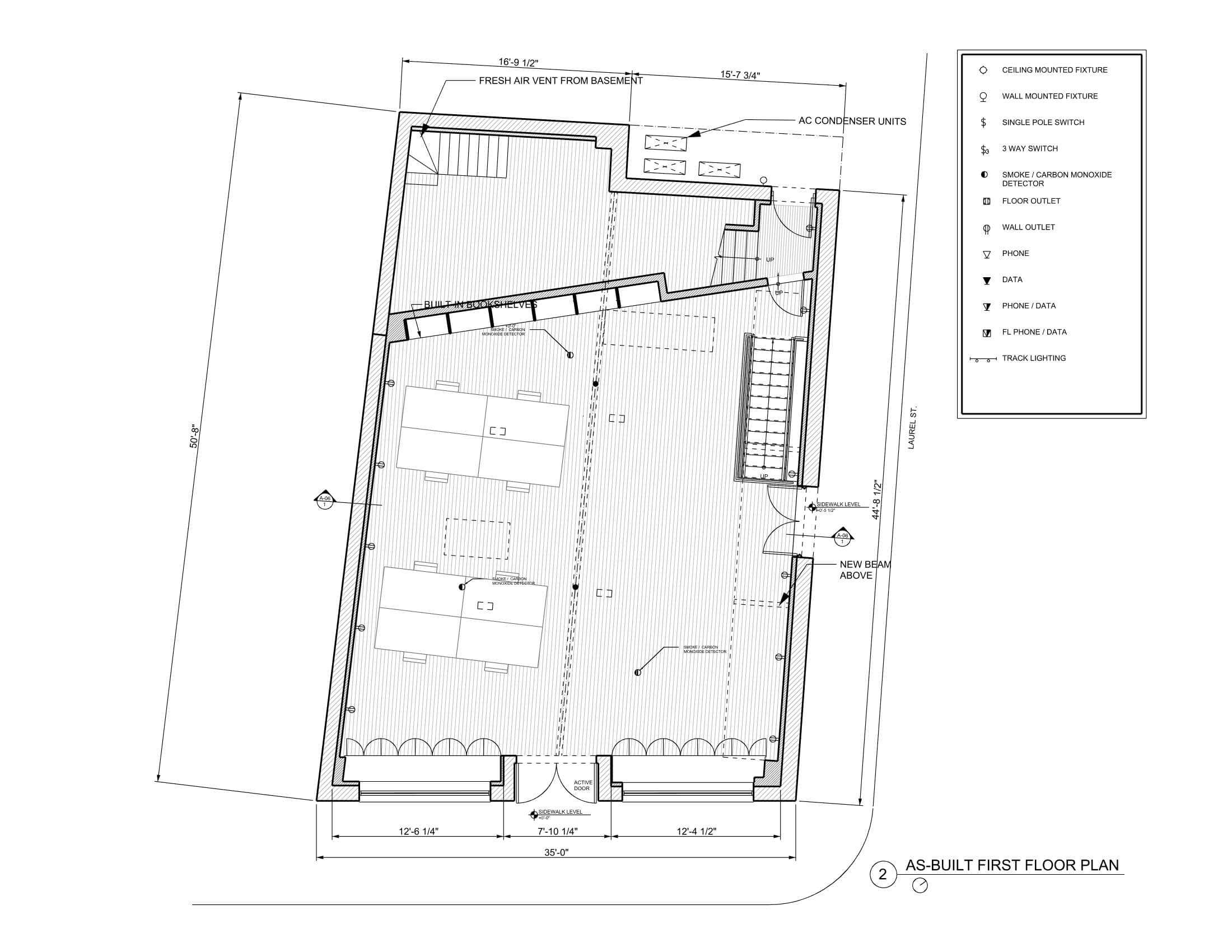

The building is directional with an unmistakable front. Originally, it was a glass fronted grocery store, a “tube space” extruded from Pleasant Street back. In the 1960s, it was converted into a floor tile warehouse and the facade was infilled with white glazed brick of the sort that Venturi likes. A loading door was inserted on the Laurel Street side in a very lewd, crude way. It was hacked out in an asymmetrical location irrespective of the side elevation’s two large symmetrically disposed brick frames.

Having two doors allowed the new interior to imply a ninety degree rotation of the plan. Whereas the original front door is centered on the existing steel structural beam and row of columns that bisects the main space, the side loading door is now centered on a new 36’ long skylight that stretches the length of the space. On the interior, the well of the skylight and the southern light it reflects on the northern wall makes the side façade more important than the old front.

The plan, rotated ninety degrees, now has two fronts, a duality that is not dictated by the logic and the morphology given to the building by the city. Re-orientation, displacement and its consequences are related to the simultaneity and flicker effect of architectural anamorphosis and the toroidal centrifugal plans of many other projects such as Goodman and Torus House, but more importantly, in this case, imply a z-axis that denies the x and y - the front and side orientations of the original building - any definitive hierarchy. The introduction of non-orientation, whereby the y axis becomes as significant as the x, equalizes the points of entry along the perimeter. The fact that the space is top lit, like a gallery, and is inward facing, in order to maximize privacy and inconspicuousness, makes the interior the primary definer of the building’s orientation.

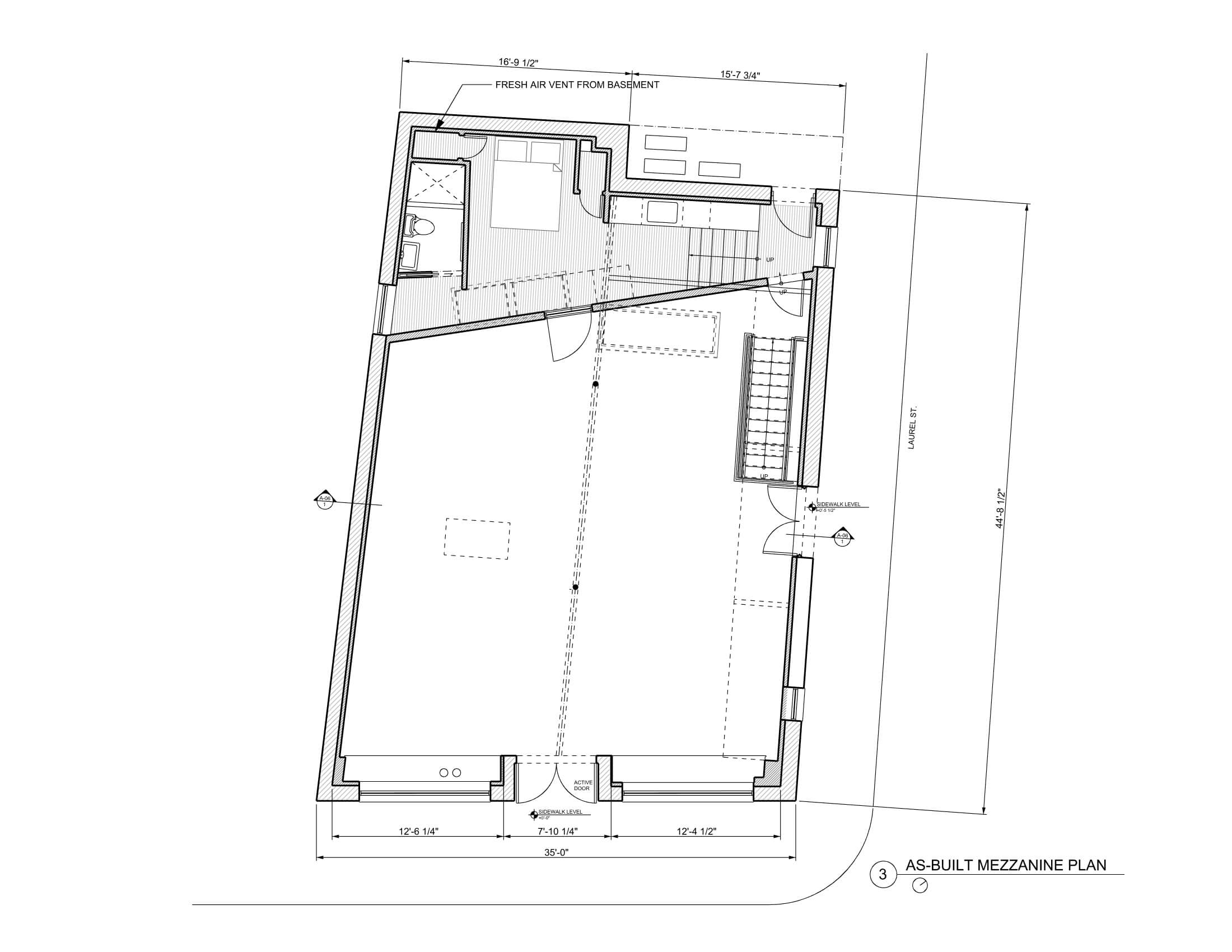

The side door, having been positioned off center, pulls the skylight along with it, away from the back of the building and in doing so, also accommodates the new, separate rear office. A new wall, angled to at once accept the length of the skylight in the main space and to accommodate the widest part of the separate office behind, also centers a small, previously inserted skylight that otherwise had no relationship to the building as a whole. That skylight had been added when the building was partitioned during its most recent use as a warehouse.

Two new steel beams have been added to support the roof that flanks the new skylight well. These beams rest upon the principle steel beam that acts as a spine running down the center of the space which in turn rests upon a steel beam that spans across the formerly glass storefront. With the addition of the new beams, the roof structure becomes triply, successively stacked.

Because the skylight produces reflected southern light, when the door in the north wall is open, the color temperature of the interior is not discernibly different than the light falling on the house across the street. As a result, interior and exterior merge. Seen from Pleasant Street through the windows on the front façade, the reflected southern light with shadows of the beams cast on the interior wall, makes the building look roofless. The shadows seem to belong to the electrical street wires. As another sign of successive architecture, this effect of emptying out suggests that the facades are a manifestation of vertical extrusion rather than surfaces enclosing a volume.

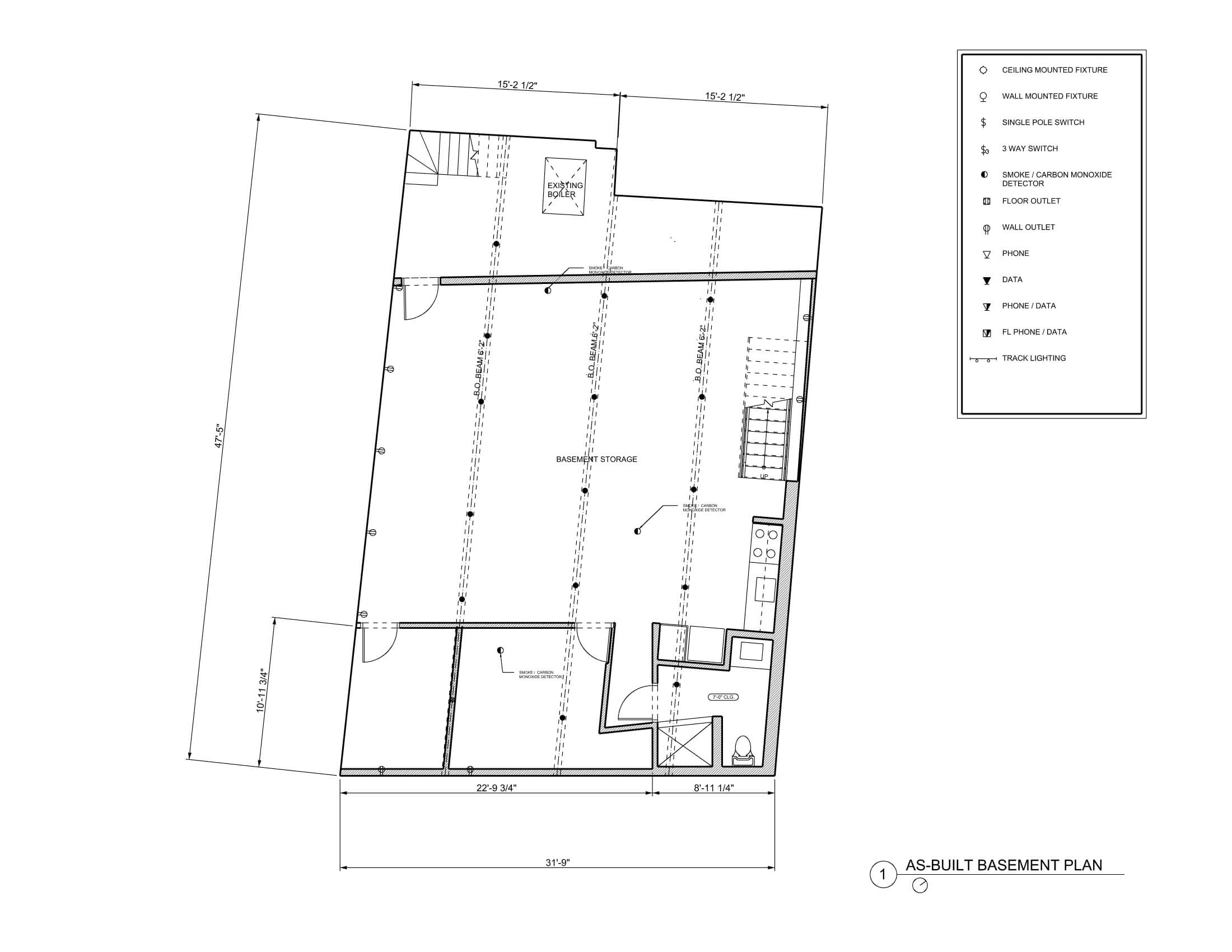

The basement is populated by irregularly distributed columns. It is as if it is the ground level space of a building on pilotis displaced downward until the floor of the main space is precisely coincident with the street. This coincidence, in turn, contributes to the seamless continuity with the outdoors.

When one enters the building, it appears to be a single room, an extreme case of isomorphism between the inside and the outside. In fact, this is an illusion. The newly added angled rear wall acts as a party wall between the main space and the rear office. During construction, the wall was pivoted slightly in order to give a window on the south façade of the building to the rear office. Note that, in the basement, the angled wall remains in its original position which allows the vertically compressed basement space to expand horizontally in an indiscernible way.

The rear office is raised a few steps. The window looks out onto the neighbor’s slightly raised rear yard garden. This bucolic setting contrasts with the view through the interior window of the angled party wall that looks out over the entire main space which when naturally top lit seems as if it is an enclosed courtyard. The patched floor recalls a parceled hardscape between disparate surrounding urban buildings.

It would be possible to imagine a linear sequence that begins with the stair rising from the basement, with flanking wall and skylight overhead, and that continues into the rear office and on up the rear office’s stair which also rises directly under a linear skylight running along the party wall. This sequence begins on the fictional ground level and concludes at the window to the garden. In this sense, the building pays homage to Villa Savoye. The other precedent for the building, according to Rafael Moneo, is the small banks of Louis Sullivan, the father of one very important solution for successive architecture as told in “The Tall Building Artistically Considered”.

Location: Cambridge, MA, USA

Client: Preston Scott Cohen, Inc.

Size: 3,000 sq. ft.

Schedule: Design 2012; Construction 2013

Program: Felxible gallery and office space

Team: Preston Scott Cohen (Design); Ashley Merchant, Carl Dworkin (project assistants); Charles Welsh (General Contractor)